Today I have officially started my new job as a Systematic Botanist at the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust in Sydney, Australia!

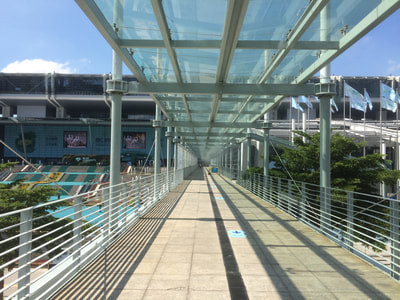

I worked here as a postdoc 11 years ago (as a Marie Curie Outgoing International Fellow) and felt completely under the charm of Australia and Sydney during that time. The Laboratoire Écologie, Systématique, Évolution (ESE) at Université Paris-Sud in France turned out to be an excellent place for me to start my academic career 8 years ago and I have been very happy in Orsay and lucky to be surrounded by wonderful colleagues there, but now is the time to start a new chapter of my life. Among the many reasons that motivated me to take the chance and apply for this new job are the unique environment and exceptional setting of my new workplace: think of a botanical garden (with many exciting living collections), a herbarium, and a molecular lab all together in one of the most spectacular central locations (pictured above, we are on the left, behind the Opera House) in a vibrant, international modern city on the edge of the Pacific with a subtropical climate. I am particularly excited to start working with a really nice set of very friendly botanists (some of whom are old friends!) from all ends of the taxonomy-evolution-ecology spectrum. And of course, I am really excited about the fascinating Australian flora, which I am going to (re-)discover, tweet about, and work on over the next few years.

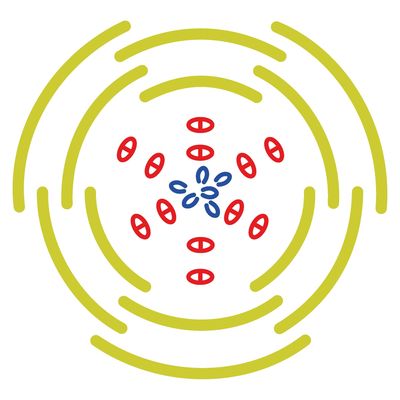

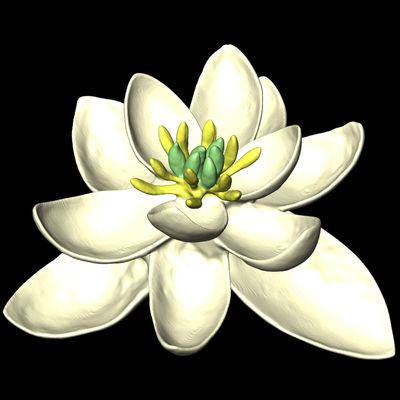

I am based at the National Herbarium of New South Wales, located in the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, one of three botanical gardens run by the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, and am officially employed by the New South Wales Government. This is a permanent research position (officially referred to as a role within the organization), with some curational duties. Compared to my previous job as Associate Professor at Université Paris-Sud, this means that I will be able to continue my research projects on eFLOWER, Magnoliidae, and Proteaceae (with increased focus on the Australian flora), but will no longer have to teach and instead will be expected to maintain up-to-date and accurate herbarium collections and databases. However, I will remain affiliated with my former lab and university for the next five years, in the context of ongoing collaborations and the supervision of Qian Zhang's PhD.

I will be looking for new students (honours, master's, PhD), postdocs, and local collaborators so feel free to contact me about ideas / opportunities to join us or visit us!

I worked here as a postdoc 11 years ago (as a Marie Curie Outgoing International Fellow) and felt completely under the charm of Australia and Sydney during that time. The Laboratoire Écologie, Systématique, Évolution (ESE) at Université Paris-Sud in France turned out to be an excellent place for me to start my academic career 8 years ago and I have been very happy in Orsay and lucky to be surrounded by wonderful colleagues there, but now is the time to start a new chapter of my life. Among the many reasons that motivated me to take the chance and apply for this new job are the unique environment and exceptional setting of my new workplace: think of a botanical garden (with many exciting living collections), a herbarium, and a molecular lab all together in one of the most spectacular central locations (pictured above, we are on the left, behind the Opera House) in a vibrant, international modern city on the edge of the Pacific with a subtropical climate. I am particularly excited to start working with a really nice set of very friendly botanists (some of whom are old friends!) from all ends of the taxonomy-evolution-ecology spectrum. And of course, I am really excited about the fascinating Australian flora, which I am going to (re-)discover, tweet about, and work on over the next few years.

I am based at the National Herbarium of New South Wales, located in the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, one of three botanical gardens run by the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, and am officially employed by the New South Wales Government. This is a permanent research position (officially referred to as a role within the organization), with some curational duties. Compared to my previous job as Associate Professor at Université Paris-Sud, this means that I will be able to continue my research projects on eFLOWER, Magnoliidae, and Proteaceae (with increased focus on the Australian flora), but will no longer have to teach and instead will be expected to maintain up-to-date and accurate herbarium collections and databases. However, I will remain affiliated with my former lab and university for the next five years, in the context of ongoing collaborations and the supervision of Qian Zhang's PhD.

I will be looking for new students (honours, master's, PhD), postdocs, and local collaborators so feel free to contact me about ideas / opportunities to join us or visit us!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed